QUESTION: While out antiquing recently I discovered a beautiful sofa that would add a lot of class to my living room. It’s in great shape, although it may eventually need to be reupholstered. The dealer said it was in the American Empire style. Although I like older things, I’m not very familiar with all the styles of furniture, especially those from the 19th century. What can you tell me about the American Empire style? Do you think this sofa will be a good investment? It isn’t all that comfortable, but I have a overstuffed one in my family room, so this one would be for more formal visits.

QUESTION: While out antiquing recently I discovered a beautiful sofa that would add a lot of class to my living room. It’s in great shape, although it may eventually need to be reupholstered. The dealer said it was in the American Empire style. Although I like older things, I’m not very familiar with all the styles of furniture, especially those from the 19th century. What can you tell me about the American Empire style? Do you think this sofa will be a good investment? It isn’t all that comfortable, but I have a overstuffed one in my family room, so this one would be for more formal visits.ANSWER: The American Empire style is one that isn’t particularly familiar to even moderate antique enthusiasts. It was more of a transitional style, and its pieces come in a wide variety of designs and ornateness.

But before looking at the American Empire style, let’s take a look at how the sofa evolved. People didn’t even know what a sofa was before 1700. They reserved chairs for important guests. Less important ones sat on stools and benches.

By the 18th century, chair makers began to pad the seats of their chairs. Some even padded the backs, but chair backs of the time were still straight and stiff. When the Queen Anne style appeared around 1750, chairs became a bit more comfortable because their backs were curved.

By the 18th century, chair makers began to pad the seats of their chairs. Some even padded the backs, but chair backs of the time were still straight and stiff. When the Queen Anne style appeared around 1750, chairs became a bit more comfortable because their backs were curved.The word sofa itself comes from the Arabic ‘soffah’, which refers to a raised part of the floor covered with rugs and cushions, while the word couch comes from the French word ‘coucher’ and literally means ‘to lay down’.

The first true sofa was the camel-back, so named for the padded hump in its back. The back, seat, and arms also had sufficient padding, making it the most comfortable seat in the room. Thomas Chippendale designed elegant camel-back sofas with simple, thick square legs that gave them stability.

By the dawn of the 19th century, the Federal style had come into vogue. Sofas became straighter, but the seats were narrower and harder. This was the age of good posture—no slouching was allowed. People had to sit up straight. Both the furniture and the clothing they wore dictated it. People back then couldn’t lean back and doze off like they can today.

By the dawn of the 19th century, the Federal style had come into vogue. Sofas became straighter, but the seats were narrower and harder. This was the age of good posture—no slouching was allowed. People had to sit up straight. Both the furniture and the clothing they wore dictated it. People back then couldn’t lean back and doze off like they can today.By the 1830s, the Empire style had gotten a hold in Europe. It took a decade or so for it to travel across the Atlantic Ocean to America. Empire sofas went a step further and rounded the back cushion so people could not lean back.

By the 1850s, people wanted more comfort in their sofas. Sofa makers angled the backs gave their pieces thicker cushions. But even these sofas still had carved wooden pieces that poked and prodded if a person didn’t sit straight.

By the 1850s, people wanted more comfort in their sofas. Sofa makers angled the backs gave their pieces thicker cushions. But even these sofas still had carved wooden pieces that poked and prodded if a person didn’t sit straight.The Mission style of the early 20th century didn’t improve much on the comfort scale. Sofas in the first two decades featured heavy, square wooden frames with a padded seat and perhaps a few loose cushions for comfort.

It wasn’t until the 1920s that the overstuffed, deep-cushioned sofa appeared. This style has existed until today in one form or another. The large, L-shaped super overstuffed versions found in today’s home are a far cry from the camel-back sofas of the 18th century.

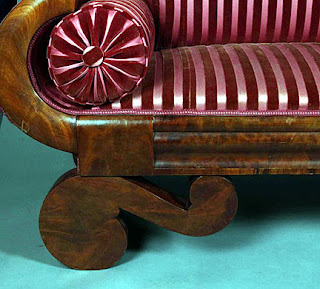

American Empire is a French-inspired Neoclassical style of American furniture and decoration that takes its name and originates from the Empire style introduced during the First French Empire period under Napoleon's rule.

It gained its greatest popularity in the U.S. after 1820. Many examples of American Empire cabinetmaking are characterized by antiquities-inspired carving—gilt-brass ormolu, and decorative inlays such as stamped-brass banding with egg-and-dart, diamond, or Greek-key patterns, or individual shapes such as stars or circles.

The most elaborate furniture in this style appeared between 1815 and 1825, often incorporating columns with rope-twist carving, animal-paw feet, anthemion, stars, and acanthus-leaf ornamentation, sometimes in combination with gilding and vert antique, an antique green simulating aged bronze. A simplified version of American Empire furniture, often referred to as the Grecian style, generally has plainer surfaces in curved forms, highly figured mahogany veneers, and sometimes gilt-stenciled decorations. Many examples of this style survive, exemplified by massive chests of drawers with scroll pillars and glass pulls, work tables with scroll feet and fiddleback chairs.

The most elaborate furniture in this style appeared between 1815 and 1825, often incorporating columns with rope-twist carving, animal-paw feet, anthemion, stars, and acanthus-leaf ornamentation, sometimes in combination with gilding and vert antique, an antique green simulating aged bronze. A simplified version of American Empire furniture, often referred to as the Grecian style, generally has plainer surfaces in curved forms, highly figured mahogany veneers, and sometimes gilt-stenciled decorations. Many examples of this style survive, exemplified by massive chests of drawers with scroll pillars and glass pulls, work tables with scroll feet and fiddleback chairs.American Empire sofas are in high demand today. Fine examples can sell for anywhere between $10,000 and $30,000. Of course, that’s for those in excellent condition and fully restored. So yes, buying one would be a good investment, as long as it’s held for at least 10 years.

To read more articles on antiques, please visit the Antiques Article section of my Web site. And to stay up to the minute on antiques and collectibles, please join the other 18,000 readers by following my free online magazine, #TheAntiquesAlmanac. Learn more about Colonial America in the Spring 2018 Edition, "Early Americana," online now.