QUESTION: At a community book sale recently, I was going through a box of old magazines and discovered a copy of The Craftsman, a magazine from the early 1900s. It looked interesting, so I put it with the rest of the items I intended to purchase and bought it. As I was going through the books and such I bought a few days later, I noticed that the publisher was Gustav Stickley. Is this the same person who made Mission furniture? Also, what can you tell me about The Craftsman?

ANSWER: It is indeed the one and the same person. And The Craftsman magazine was Stickley’s pride and joy and the first of its kind to discuss home improvement and design.

Gustav Stickley was one of the most important figures in the Arts and Crafts Movement in the United States. He was a furniture maker who became a leader in the philosophy of the Arts and Crafts Movement as well as in the production of objects suitable for use that followed its principles. And although he wasn’t a craftsman himself, he successfully inspired craftsmen to carry out his concepts.

Also, he knew the value of publicity in selling his products and his ideas. He used his magazine, entitled The Craftsman, which he edited and published during the 15 years he was active in the Movement, as his main means of promotion. At its peak, The Craftsman reached 60,000 subscribers and featured articles and essays on Stickley's many interests and concerns.

Also, he knew the value of publicity in selling his products and his ideas. He used his magazine, entitled The Craftsman, which he edited and published during the 15 years he was active in the Movement, as his main means of promotion. At its peak, The Craftsman reached 60,000 subscribers and featured articles and essays on Stickley's many interests and concerns.Gustav Stickley often referred to himself as "the craftsman" and used the term "craftsman" in many ways. The furniture he sold was Craftsman—not "mission"—furniture, his version of the Arts and Crafts movement was the Craftsman Movement, and his monthly magazine was The Craftsman.

He published the first issue of his magazine in October 1901 in Eastwood, New.York, where he had located his furniture factory. Later he moved The Craftsman to Syracuse and finally to New York City. The premier issue emphasized the work and ideas of William Morris through an article entitled “William Morris, Some Thoughts Upon His Life.”

Irene Sargent, professor of art history at the University of Syracuse, served as Stickley's principal editor. She wrote many of the articles in the magazine’s early years. A very persuasive person, Stickley was able to obtain contributions from such notables as Louis Sullivan, Jacob Riis, Leopold Stokowski, John Burroughs, and Jane Addams. They covered a wide variety of subject matter, from architecture to art and nature, as well as the concepts of social reform prevalent at the time.

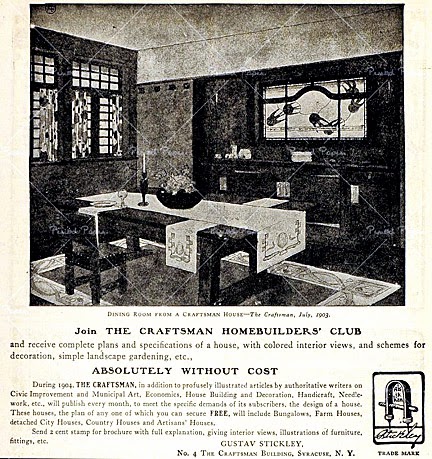

Though he was an idealist, Gustav Stickley had to eat. The Craftsman offered him lots of advertising space for his growing furniture business. Thirteen pictures of furniture made by Stickley's company, United Crafts, included a round table, an armchair, and a settle, followed an article entitled “An Argument for Simplicity in Household Furnishings” in the first issue. The Craftsman also showed readers how to use the furniture in its many illustrations of room settings. Over the years, Stickley added metalwork, lighting fixtures, textiles and other items to his product line, and also to The Craftsman.

Though he was an idealist, Gustav Stickley had to eat. The Craftsman offered him lots of advertising space for his growing furniture business. Thirteen pictures of furniture made by Stickley's company, United Crafts, included a round table, an armchair, and a settle, followed an article entitled “An Argument for Simplicity in Household Furnishings” in the first issue. The Craftsman also showed readers how to use the furniture in its many illustrations of room settings. Over the years, Stickley added metalwork, lighting fixtures, textiles and other items to his product line, and also to The Craftsman. He often commented on the Craftsman ideal. Stickley believed an ideal kind of life encompassed beauty, economy, reason, comfort, and progress. It didn’t satisfy him to merely achieve this ideal in furniture but he felt that consumers must also have the right kind of houses in which to place the furniture. He no sooner began designing Craftsman houses than he realized that people wanted Craftsman fabrics and accessories of all kinds. In other words, he believed in the concept of total interior design.

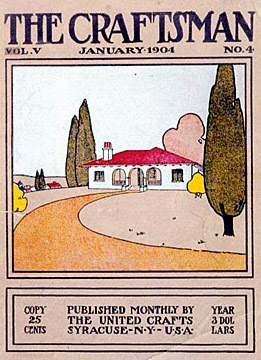

While early issues had somewhat smaller covers, ones beginning in 1913 had larger ones measuring 8 by 11 inches. Stickley printed all of them on brown or tan stock and usually featured a wood block decoration in two or more colors, initialed by the artist. Each issue consisted of 100-140 white and glossy pages, and later ones had as many as 175 pages.

Plans for Craftsman houses, some small and simple, others more elaborate, attributed to Stickley as the architect, although he had no architectural training. People built many of these houses using Stickley’s plans. The Craftsman also featured short fiction and poetry, as well as the work of famous photographers.

Plans for Craftsman houses, some small and simple, others more elaborate, attributed to Stickley as the architect, although he had no architectural training. People built many of these houses using Stickley’s plans. The Craftsman also featured short fiction and poetry, as well as the work of famous photographers.Besides articles about Stickley’s products, The Craftsman often included ones about other makers of Arts and Crafts objects. For example, a 1903 article, “An Art Industry of the Bayous: The Pottery of Newcomb College” by Irene Sargent, documents the early history of Newcomb pottery. Photographs of the pottery school and examples of early high glaze pieces accompanied it. There were also essays devoted to philosophical, political and social commentary, usually promoting the simple life

The magazine also offered all kinds of practical and how-to advice, from gardening to leather tooling to embroidery to purchasing household appliances.

It also included advertisements by manufacturers whose products are now greatly valued by collectors, for example, Rookwood pottery, Heisey glassware, Handel lamps, and Homer Laughlin china.

Unfortunately, Stickley overextended himself and in 1915 had to file for bankruptcy. But The Craftsman was the first periodical to emphasize the importance of harmony in a home’s interior, harmony which was to be created through attention paid to walls, floors, windows, textiles, small objects and furniture.