QUESTION: I’m a great lover of all things Art Deco, although I don’t know much about it. I’ve heard some people refer to this style as Streamlined Modern while other call it Art Moderne. Can you please tell me a little about this style? And what about Streamlined Modern? Is it related to Art Deco?

QUESTION: I’m a great lover of all things Art Deco, although I don’t know much about it. I’ve heard some people refer to this style as Streamlined Modern while other call it Art Moderne. Can you please tell me a little about this style? And what about Streamlined Modern? Is it related to Art Deco?

ANSWER: Art Deco and Art Moderne overlap, both stylistically and chronologically. Both were in vogue in the first half of the 20th century. But it's more a question of style than dates. While Art Deco emphasized verticality and stylized, geometric ornamentation, Art Moderne was a horizontal design, emphasizing movement and sleekness;.

The Art Deco style made its debut at the 1925 World's Fair in Paris—the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes or the International Exhibition of Modern and Industrial Decorative Arts—but the term Art Deco wasn’t used until 1966. A group of French architects and interior designers, who banded together to form the Societe des Artistes Decorateurs, developed the style to incorporate elements of style from diverse modern artworks and current fashion trends. Influence from Cubism and Surrealism, Egyptian and African folk art can be seen in the lines and embellishments, and Asian influences contribute symbolism, grace and detail.

The Art Deco style made its debut at the 1925 World's Fair in Paris—the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes or the International Exhibition of Modern and Industrial Decorative Arts—but the term Art Deco wasn’t used until 1966. A group of French architects and interior designers, who banded together to form the Societe des Artistes Decorateurs, developed the style to incorporate elements of style from diverse modern artworks and current fashion trends. Influence from Cubism and Surrealism, Egyptian and African folk art can be seen in the lines and embellishments, and Asian influences contribute symbolism, grace and detail.

Art Deco was already an internationally mature style by 1925—one that had flourished in the years following World War I and peaked at the time of the fair. The enormous commercial success of Art Deco ensured that designers and manufacturers throughout Europe continued to promote this style until well into the 1930s.

Art Deco was already an internationally mature style by 1925—one that had flourished in the years following World War I and peaked at the time of the fair. The enormous commercial success of Art Deco ensured that designers and manufacturers throughout Europe continued to promote this style until well into the 1930s.

Sometimes Deco designers applied ornamentation to the surface of an object, like a decorative skin, but at other times the utilitarian designs of bowls, plates, vases, and furniture were themselves purely ornamental. These objects weren’t intended for practical use but rather created for their decorative value alone, exploiting the beauty of form or material. Among the most popular and recurring motifs were the human figure, animals, flowers, and plants. Abstract geometric decoration was also common.

Victorians loved to apply ornamentation onto furniture, to embellish basic frames and shapes. With Art Deco, the texture and embellishment came from contrasts in a variety of colored woods and inlays or in the material itself. Designers often used burled or birds-eye or visibly grained woods, tortoise shell, ivory, tooled leathers. Lacquered glosses accentuated color differences. Animal skins and patterned fabrics in bright colors were also popular as upholstery.

Victorians loved to apply ornamentation onto furniture, to embellish basic frames and shapes. With Art Deco, the texture and embellishment came from contrasts in a variety of colored woods and inlays or in the material itself. Designers often used burled or birds-eye or visibly grained woods, tortoise shell, ivory, tooled leathers. Lacquered glosses accentuated color differences. Animal skins and patterned fabrics in bright colors were also popular as upholstery.

Though it spread to other countries, Art Deco was a distinctively French response to the postwar demand for luxurious objects and fine craftsmanship. French designers utilized lavish materials and such rich, traditional decorative techniques as inlay and veneer on streamlined geometric forms.

Art Deco reflected the general optimism and carefree mood that swept Europe and the United States following World War I. Hope and prosperity are represented in sunburst designs, chevrons and references to the good life in the elegant figures depicted in casual, sensual poses, often dancing or sipping cocktails. The modern influences heralded a bright and shining future outlook that found its way to architecture, jewelry, automobile design and even extended to ordinary things such as refrigerators and trash cans.

Art Deco reflected the general optimism and carefree mood that swept Europe and the United States following World War I. Hope and prosperity are represented in sunburst designs, chevrons and references to the good life in the elegant figures depicted in casual, sensual poses, often dancing or sipping cocktails. The modern influences heralded a bright and shining future outlook that found its way to architecture, jewelry, automobile design and even extended to ordinary things such as refrigerators and trash cans.

Exoticism also played a role in Art Deco. During the 1920s and 1930s, the French government encouraged designers to take advantage of resources—like raw materials and a skilled workforce—that could be imported from the nation's colonies in Asia and Africa. The resulting growth of interest in the arts of colonial countries in Asia and Africa led French designers to explore new materials, such as ivory, sharkskin, and exotic woods, techniques such as lacquering and ceramic glazes, and forms that evoked faraway places and cultures.

Art Moderne

Art Moderne

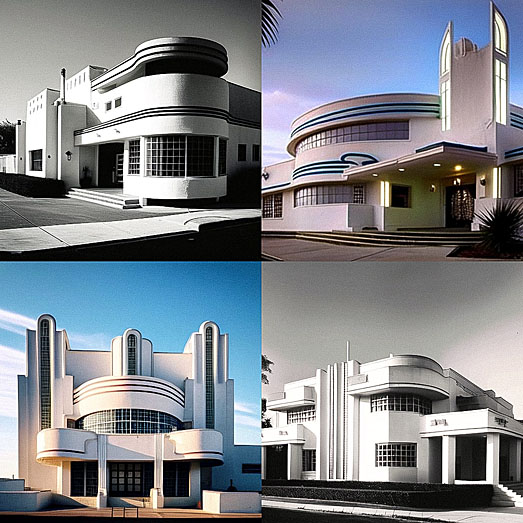

Moderne, also called Streamlined Modern, was an American invention that first appeared in the 1930s and lasted into the 1940s. Although taking its design concepts from Art Deco, it was a completely different style It was bigger and bolder. While Art Deco placed an emphasis on shape, Art Moderne was streamlined. Unfortunately, this is the style most Americans confuse with Art Deco.

Think of Art Moderne as Art Deco on steroids. Moderne was positively streamlined—at the time a new scientific theory that shaping objects along curving lines to cut wind resistance would make them move more efficiently. The furniture in this style was much more pared down, making its outline more geometric in sleek curves like a tear drop or torpedo. Moderne designers often conceived pieces as a series of escalating levels- similar to a staircase or the setback effect of skyscrapers that were rising in every city.

While rich colors, bold geometry, and decadent detail work characterized Art Deco, evoking glamour, luxury, and order with symmetrical designs in exuberant shapes, Art Moderne was essentially a machine-made style focused on mass production, functional efficiency, and a more abstract look coming from the Bauhaus in Germany.

While rich colors, bold geometry, and decadent detail work characterized Art Deco, evoking glamour, luxury, and order with symmetrical designs in exuberant shapes, Art Moderne was essentially a machine-made style focused on mass production, functional efficiency, and a more abstract look coming from the Bauhaus in Germany.

Much of it was designed to be mass-produced, but even if it wasn't, it looked as if it could be: Art Deco's balance and proportion extended to regularity and repetition. Much of the decorative interest in a Moderne piece comes from the precision of line and duplication of functional features. Art Moderne designs often conveyed a sense of motion.

Art Moderne designers favored simpler, aerodynamic lines and forms in the modeling of ships, airplanes, and automobiles. In the modern machine age smooth surfaces, curved corners, and an emphasis on horizontal lines came into fashion. Streamlining appeared on everyday objects and buildings such as roadside diners, motor hotels, movie theaters, early strip malls and shopping centers, seaside marinas, and air and bus terminals. Trains, ocean liners, airplane fuselages, as well as luxury automobiles all sported the Moderne look.

People often refer to furnishings and buildings from the 1920s through the 1940s as Art Deco. Understanding the difference between Art Deco and Art Moderne isn't always easy, especially since Art Deco was originally called Moderne.

To read more articles on antiques, please visit the Antiques Articles section of my Web site. And to stay up to the minute on antiques and collectibles, please join the over 30,000 readers by following my free online magazine, #TheAntiquesAlmanac. Learn more about "The Age of Photography" in the 2023 Holiday Edition, online now. And to read daily posts about unique objects from the past and their histories, like the #Antiques and More Collection on Facebook.