QUESTION: For several years I’ve been searching for older ornaments for my Christmas tree. I’ve seen a good number at flea markets and antique cooperatives. Many of these are still in their original boxes marked “Shiny Brite.” I’d like to know more about this company. When did they produce ornaments and what kind did they produce?

QUESTION: For several years I’ve been searching for older ornaments for my Christmas tree. I’ve seen a good number at flea markets and antique cooperatives. Many of these are still in their original boxes marked “Shiny Brite.” I’d like to know more about this company. When did they produce ornaments and what kind did they produce?

ANSWER: Today, the trend is to decorate Christmas trees with handcrafted ornaments, from simpler ones sold at church bazar to finely crafted ones of wood, silver, and gold sold at Christmas markets throughout the world. But some people prefer to decorate their trees with nostalgic glass ornaments from their childhood.

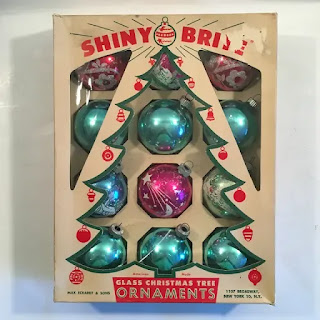

Ornaments that decorated yesterday’s trees continue to create holiday traditions. Shiny glass orbs hang from branches in bright, shiny colors, and sparkly patterns. Shiny Brite was a mid-20th-century brand created by German-American immigrant Max Eckardt.

Ornaments that decorated yesterday’s trees continue to create holiday traditions. Shiny glass orbs hang from branches in bright, shiny colors, and sparkly patterns. Shiny Brite was a mid-20th-century brand created by German-American immigrant Max Eckardt.

Blown-glass Christmas ornaments with hand-painted accents got their start in the German village of Lauscha in the 1840s. Glassmakers blew molten glass into molds shaped like fruit and nuts, then silvered the inside with a special compound of silver nitrate and sugar water.

As a native of a small village near Lauscha, Eckhardt knew the appeal of glass ornaments and also saw their potential in the American market. He had been importing hand-blown glass balls from his homeland since the early 20th century. He had the foresight to anticipate a disruption in his supply of glass from Germany from the upcoming World War II and in 1937, he established the Shiny Brite Company in New York. The silver nitrate coating on the insides of his ornaments inspired him to name his company Shiny Brite.

As a native of a small village near Lauscha, Eckhardt knew the appeal of glass ornaments and also saw their potential in the American market. He had been importing hand-blown glass balls from his homeland since the early 20th century. He had the foresight to anticipate a disruption in his supply of glass from Germany from the upcoming World War II and in 1937, he established the Shiny Brite Company in New York. The silver nitrate coating on the insides of his ornaments inspired him to name his company Shiny Brite.

To keep his company afloat, Eckhardt sought the help of New York’s Corning Glass Company, with the promise that F.W. Woolworth would place a large order if Corning could modify its glass ribbon machine, which made light bulbs, to produce ornaments. This machine, built in 1926, produced 2,000 light bulbs per minute. The transition was a success, and Woolworth’s ordered more than 235,000 ornaments. In December 1939,Eckhardt shipped the first machine-made batch to its 5-and-10-Cent Stores, where they sold for 2 to 10 cents each.

To keep his company afloat, Eckhardt sought the help of New York’s Corning Glass Company, with the promise that F.W. Woolworth would place a large order if Corning could modify its glass ribbon machine, which made light bulbs, to produce ornaments. This machine, built in 1926, produced 2,000 light bulbs per minute. The transition was a success, and Woolworth’s ordered more than 235,000 ornaments. In December 1939,Eckhardt shipped the first machine-made batch to its 5-and-10-Cent Stores, where they sold for 2 to 10 cents each.

By 1940, Corning was producing 300,000 unadorned ornaments per day, sending the clear glass balls to outside artists, including those at Eckardt’s factories, to be hand decorated. After being lined with silver nitrate, the ornaments ran through a lacquer bath, received decoration from Eckardt’s employees and packaging in brown cardboard boxes. According to a LIFE magazine article from December 1940, Corning Glass Works expected to produce 40 million ornaments by the end of that year, supplying 100 percent of the domestic ornament market.

By 1940, Corning was producing 300,000 unadorned ornaments per day, sending the clear glass balls to outside artists, including those at Eckardt’s factories, to be hand decorated. After being lined with silver nitrate, the ornaments ran through a lacquer bath, received decoration from Eckardt’s employees and packaging in brown cardboard boxes. According to a LIFE magazine article from December 1940, Corning Glass Works expected to produce 40 million ornaments by the end of that year, supplying 100 percent of the domestic ornament market.

Originally, the ornaments were plain silver, but eventually Eckardt produced them in a large variety of colors: with classic red the most popular color in the 1940s, followed by green, gold, pink and blue, both in solids and stripes. The company also offered Shiny Brite ornaments in a variety of shapes besides balls, including tops, bells, icicles, teardrops, trees, finials, pine cones, and Japanese lanterns, and reflectors. Workers decorated some with mica “snow.”

Through the 1940s and 1950s, Shiny Brite ornaments became the most popular tree ornaments in the U.S. Eckhardt stressed that they were American-made as a selling point during World War II by featuring Uncle Sam shaking hands with Santa on the front of the original 1940's boxes.

Corning continued to crank out Shiny Brite ornaments, and by the 1950s, production reached a rate of 1,000 per minute; with machines also painting them at that time. The 1950s was the peak of Shiny Brite production and popularity, with Eckardt operating four New Jersey factories to keep pace with the demand.

Corning continued to crank out Shiny Brite ornaments, and by the 1950s, production reached a rate of 1,000 per minute; with machines also painting them at that time. The 1950s was the peak of Shiny Brite production and popularity, with Eckardt operating four New Jersey factories to keep pace with the demand.

Shiny Brite ornaments dangled from trees through the early 1960s, until plastic ornaments became more popular. But over the years, vintage Shiny Brites have remained popular with collectors for their beauty and nostalgia, and acting as a sort of time capsule of American holiday history. They are some of the most sought after vintage ornaments from the mid 20th century and are the perfect decoration for those Space-Age aluminum trees.

To read more articles on antiques, please visit the Antiques Articles section of my Web site. And to stay up to the minute on antiques and collectibles, please join the over 30,000 readers by following my free online magazine, #TheAntiquesAlmanac. Learn more about "The Age of Photography" in the 2023 Holiday Edition, online now. And to read daily posts about unique objects from the past and their histories, like the #Antiques and More Collection on Facebook.