QUESTION: I’ve been fascinated with food containers, especially old ones since I was a young adult. When I go to the supermarket, I’m amazed at the variety of the packaging. In that sea of colors and textures, I wonder how I find the items I need. I like to browse through antique cooperatives. Many of the booths selling old kitchenware also have a variety of old food containers—cans, boxes, and tins. What is the origin of food packaging? How did it develop over the decades? And how collectible is it?

QUESTION: I’ve been fascinated with food containers, especially old ones since I was a young adult. When I go to the supermarket, I’m amazed at the variety of the packaging. In that sea of colors and textures, I wonder how I find the items I need. I like to browse through antique cooperatives. Many of the booths selling old kitchenware also have a variety of old food containers—cans, boxes, and tins. What is the origin of food packaging? How did it develop over the decades? And how collectible is it?

ANSWER: Food containers have been around for over 200 years. At first they were basic but over time food packaging developed into a necessary form of distribution. Not only did the containers keep the food fresh, the labels on the outside helped to advertise the product on store shelves.

Because the focus of the Industrial Revolution was on mass production and distribution, food packaging had to be durable, easy to produce, and accessible. Food preservation was also a high priority, as new transportation methods allowed businesses to ship it further.

Because the focus of the Industrial Revolution was on mass production and distribution, food packaging had to be durable, easy to produce, and accessible. Food preservation was also a high priority, as new transportation methods allowed businesses to ship it further.

Back in 1875, French General Napoleon Bonaparte offered 12,000 francs to anyone who could preserve food for his army. This led confectioner Nicholas Appert to invent the first “canning” technique that sealed cooked food in glass containers and boiled them for sterilization.

Later in 1810, British inventor Peter Durand patented his own canning method using tin instead of glass. By 1820 he was supplying canned food to the Royal Navy in large quantities.

The second half of the 19th century brought further developments in manufacturing and production—among which included food packaging. In 1856, corrugated paper first appeared in England as a liner for tall hats. By the early 1900s, shipping cartons made of it replaced wooden crates and boxes.

The second half of the 19th century brought further developments in manufacturing and production—among which included food packaging. In 1856, corrugated paper first appeared in England as a liner for tall hats. By the early 1900s, shipping cartons made of it replaced wooden crates and boxes.

In 1890, the National Biscuit Company, now known as Nabisco, individually packaged its biscuits in the first packaging to preserve crispness by providing a moisture barrier. Kellogg’s introduced the first cereal box for corn flakes in 1906, eighty-nine years after the first commercial cardboard box appeared in England.

Leo Hendrik Baekeland invented the first plastic, known as Bakelite, based on a synthetic polymer in 1907. It could be shaped or molded into almost anything, providing endless packaging possibilities.

Eventually, food manufacturers began using packaging containers that consumers were reluctant to discard. A tin of Sultana Peanut Butter, which came in a large pail with wire handles, made the perfect sand bucket to take to the beach in summer. Other similar containers included the log-cabin-shaped tin holding Log Cabin Syrup. People reused biscuit tins to hold everything from petty cash to old buttons and homemade cookies.

Eventually, food manufacturers began using packaging containers that consumers were reluctant to discard. A tin of Sultana Peanut Butter, which came in a large pail with wire handles, made the perfect sand bucket to take to the beach in summer. Other similar containers included the log-cabin-shaped tin holding Log Cabin Syrup. People reused biscuit tins to hold everything from petty cash to old buttons and homemade cookies.

Lambrecht butter, found primarily east of the Mississippi, came packaged in an attractive gray or white stoneware tub with blue script while Kaukauna Klub cheddar cheese came in a clay crock with a heavy wire clamp.

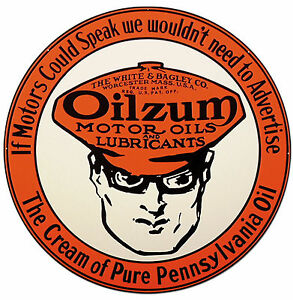

By the dawning of the 20th century, package design was an important way to draw attention to a product. Manufacturers of drugs, paint, oil, as well as food items worked to establish a visual logo or trademark. Labels and magazines ads were the only means of communicating the goodness of a product.

One of the first national trademarks was the Uneeda boy, a little boy in a yellow slicker that represented freshness from the elements. Soon after came the Morton Salt girl, Aunt Jemima, Dutch boy, the Fisk Tire boy in Dr. Dentons holding a candle, and many other memorable logos. These symbols are all very collectible today.

One of the first national trademarks was the Uneeda boy, a little boy in a yellow slicker that represented freshness from the elements. Soon after came the Morton Salt girl, Aunt Jemima, Dutch boy, the Fisk Tire boy in Dr. Dentons holding a candle, and many other memorable logos. These symbols are all very collectible today.

The widespread practice of packing food in tin cans and containers was a direct result of the public's acceptance of the Germ Theory of Disease. In the 19th century, many Americans were still oblivious to the research done by Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch in food preservation.

Today, some people look down on those who eat canned or processed food as something people without access to fresh food eat. But in the late 19th century, food in tins was highly desirable. Consumers considered it more sanitary, and therefore healthier, than food offered in bins or barrels at the General Store. That’s when branding became particularly important; customers learned they could expect a certain level of quality from, say, Kellogg’s.

At first, manufacturers covered tinplate containers with paper labels, which had a product’s pertinent information and advertising stenciled or printed on them. Machines that could trim and stamp sheets of tin had been introduced around 1875, and between 1869 and 1895, manufacturers developed a process that allowed them to use lithography to transfer images directly onto the tin containers. Coffee and tea, as well as tobacco and beverages and snack foods came packaged in tins.

At first, manufacturers covered tinplate containers with paper labels, which had a product’s pertinent information and advertising stenciled or printed on them. Machines that could trim and stamp sheets of tin had been introduced around 1875, and between 1869 and 1895, manufacturers developed a process that allowed them to use lithography to transfer images directly onto the tin containers. Coffee and tea, as well as tobacco and beverages and snack foods came packaged in tins.

Today, all sorts of historic food packaging is collectible. In fact, it’s one of the most affordable and pleasurable of collectibles.

Today, all sorts of historic food packaging is collectible. In fact, it’s one of the most affordable and pleasurable of collectibles.

To read more articles on antiques, please visit the Antiques Articles section of my Web site. And to stay up to the minute on antiques and collectibles, please join the over 30,000 readers by following my free online magazine, #TheAntiquesAlmanac. Learn more about the "Pottery Through the Ages" in the 2022 Winter Edition, online now. And to read daily posts about unique objects from the past and their histories, like the #Antiques and More Collection on Facebook.