QUESTION: As with many people today, my husband and I have moved several times since graduating from college and now live over 1,000 miles from my parents. At times, I do get a bit homesick for my hometown, even though I try to visit when I can. Recently, while searching for some old postcards on the Internet, I came across several from my hometown. On a subsequent phone call, I mentioned my finds to my mother. She said she had several items, including a souvenir history booklet sold during our town’s sesquicentennial celebration. I’m interested in starting a collection of memorabilia from my hometown. How do I go about it, being that I live so far away?

QUESTION: As with many people today, my husband and I have moved several times since graduating from college and now live over 1,000 miles from my parents. At times, I do get a bit homesick for my hometown, even though I try to visit when I can. Recently, while searching for some old postcards on the Internet, I came across several from my hometown. On a subsequent phone call, I mentioned my finds to my mother. She said she had several items, including a souvenir history booklet sold during our town’s sesquicentennial celebration. I’m interested in starting a collection of memorabilia from my hometown. How do I go about it, being that I live so far away?

ANSWER: Collecting hometown memorabilia is not only fun but can be very enlightening. Most people really don’t know all that much about where they were born. And in today’s mobile society, a lot of them move on to several other places during their lifetimes. So just where do you begin?

ANSWER: Collecting hometown memorabilia is not only fun but can be very enlightening. Most people really don’t know all that much about where they were born. And in today’s mobile society, a lot of them move on to several other places during their lifetimes. So just where do you begin?

The first thing to do is investigate the history of your city, town, or village. This will give you clues to your community’s identity. Many places changed their names more than once during their lifetime.

Just as if you were compiling your family’s social history, so should you begin at your town’s county library and historical society. Both offer knowledgeable resources of information that will help you in your search. If you live a good distance away, you may find links to both on the Internet, but a direct phone call is your best method of making contact. Once you have your foot in the door, you can use Email or messaging to exchange questions and answers.

As people move farther and farther away from home, there seems to be a need to possess artifacts of that place. Historical societies publish newsletters, plus you may even find someone in your town has published a local history. And knowing the history of your town is the key to finding its memorabilia.

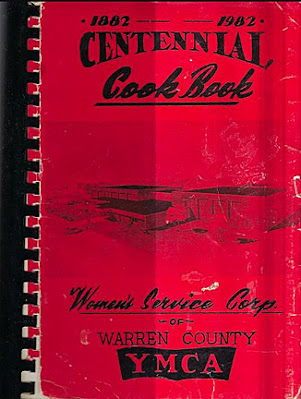

As cities, towns, and villages celebrate their founding anniversaries, they often publish a history booklet that they sell to help pay for the celebration. Sometimes, it’s just a small booklet, but at other times, the town’s newspaper will comb through it’s archives for interesting stories and publish a book of them. This was very popular during the early to mid-20th century.

As cities, towns, and villages celebrate their founding anniversaries, they often publish a history booklet that they sell to help pay for the celebration. Sometimes, it’s just a small booklet, but at other times, the town’s newspaper will comb through it’s archives for interesting stories and publish a book of them. This was very popular during the early to mid-20th century.

If you haven't moved away from home yet, start saving items now that have significance to you. It’s possible that you may already have some items. The old screwdriver packed in an old toolbox sports a Bakelite handle and the telephone number and advertising logo of a local lumber yard. Decorative paper fans from the county fair grace a hall mirror. Search through old housewares, sewing boxes and tool chests. Advertising collectibles evolve from items that eventually become more sentimental than utilitarian.

Rescuing an item that’s headed for the dump is one of the most exciting and economical ways to collect hometown memorabilia. Perhaps a grandparent or older relative has died and you volunteer to help sort out their belongings or the contents of their house. As you do so, keep a watchful eye out for memorabilia of your town.

Rescuing an item that’s headed for the dump is one of the most exciting and economical ways to collect hometown memorabilia. Perhaps a grandparent or older relative has died and you volunteer to help sort out their belongings or the contents of their house. As you do so, keep a watchful eye out for memorabilia of your town.

Souvenir glassware can often be found in cupboards, especially ruby-flashed little cups, glasses, and pitchers with the town’s name and date etched into the red coating. If your town is a tourist destination, you’ll find all sorts of items available with the its name imprinted on them.

And don’t forget to spread the word to older relatives and friends. Both can be an excellent source of hometown collectibles. When people have to move to smaller quarters, they often look for a home for possessions that might have largely sentimental value.

When all else fails, you can always buy that special hometown collectible. If your community ever contained any type of commercial, civic or church structure, there’s bound to be some advertising memorabilia or paper items connected to it. As you search, you may want to broaden your collection.

When all else fails, you can always buy that special hometown collectible. If your community ever contained any type of commercial, civic or church structure, there’s bound to be some advertising memorabilia or paper items connected to it. As you search, you may want to broaden your collection.

Another readily available item is postcards. They’re one of the most popular and plentiful hometown collectibles. Photography flourished in the first quarter of the 20th century and there was a big business in printing inexpensive postcards that would put tiny towns on the map—at least locally. Hometown pride was high and if its claim to fame was a grain elevator near the railroad tracks or a post office with the flag unfurled, some enterprising artist sketched or photographed it.

Most postcards of this type range from $1 to $20 with real photo postcards being at the high end. Where you buy the card also affects the price. Flea market and garage sale dealers often have a box of assorted old postcards on their tables. Since they don’t catalog them, they’ll most likely sell for less. Postcard and mid-range antique shows are another good source. And don’t forget eBay and other online auction sites.

Most postcards of this type range from $1 to $20 with real photo postcards being at the high end. Where you buy the card also affects the price. Flea market and garage sale dealers often have a box of assorted old postcards on their tables. Since they don’t catalog them, they’ll most likely sell for less. Postcard and mid-range antique shows are another good source. And don’t forget eBay and other online auction sites.

And just with antiques, if you frequent a postcard dealer at a general, regularly scheduled antique show, let him know what town you’re interested in, and he or she may start putting cards back for you.

Churches and schools, the cornerstones of many small communities, also produced many mementos, including programs of special functions, graduation invitations, awards, meeting minutes and photographs of school groups and church confirmation classes. Granges and civic associations brought neighbors together for community improvement and fellowship and also left a rich reserve of paper items.

Churches and schools, the cornerstones of many small communities, also produced many mementos, including programs of special functions, graduation invitations, awards, meeting minutes and photographs of school groups and church confirmation classes. Granges and civic associations brought neighbors together for community improvement and fellowship and also left a rich reserve of paper items.

Like paper items, commonly referred to as ephemera, advertising collectibles can often be found at specialty shows as well as at general shows. With some brand name advertising collectibles, the addition of a small-town name on the item may actually make it more expensive because it is specialized and rarer Advertising collectibles are a hot field and the casual collector should do some homework before entering the market.

You may not be able to go home again, but you can certainly bring home some great hometown collectibles.

To read more articles on antiques, please visit the Antiques Articles section of my Web site. And to stay up to the minute on antiques and collectibles, please join the over 30,000 readers by following my free online magazine, #TheAntiquesAlmanac. Learn more about militaria in the 2022 Fall Edition, with the theme "After-Battle Antiques," online now. And to read daily posts about unique objects from the past and their histories, like the #Antiques and More Collection on Facebook.