QUESTION: Recently, while browsing a local antique show, I came across a dealer with a display of oddly looking little pieces. They didn’t seem to have any function and each had a large hole or cavity, so I asked her what they were. She said they were pocket watch holders. I had never seen anything like them before since pocket watches went out of style in the mid 20th century. Why would a person need a pocket watch holder? Wouldn’t they just place their pocket watch on a chest top or nightstand at the end of the day? What can you tell me about these curious little items?

QUESTION: Recently, while browsing a local antique show, I came across a dealer with a display of oddly looking little pieces. They didn’t seem to have any function and each had a large hole or cavity, so I asked her what they were. She said they were pocket watch holders. I had never seen anything like them before since pocket watches went out of style in the mid 20th century. Why would a person need a pocket watch holder? Wouldn’t they just place their pocket watch on a chest top or nightstand at the end of the day? What can you tell me about these curious little items?

ANSWER: During the 19th Century people used pocket watch holders, often referred to as a watch hutches, to hang their pocket watches in overnight to protect them from loss or damage—it’s better for the watch mechanism if it hangs vertically rather than lying flat. These watch holders also converted any pocket watch into small table or mantel clocks in a room that didn't contain a clock. They also made perfect bedside clocks, before the advent of alarm clocks.

During the second half of the 19th Century, cast iron was the most common material for making pocket watch holders. Artisans covered these unsightly cast pieces with gilded bronze to simulate gold. Artisans sculpted the original designs to represent forms in nature, such as vines and leaves or figural representations of country life. Mounted on a marble base and standing between 7 and 8 inches tall, they were quite heavy.

During the second half of the 19th Century, cast iron was the most common material for making pocket watch holders. Artisans covered these unsightly cast pieces with gilded bronze to simulate gold. Artisans sculpted the original designs to represent forms in nature, such as vines and leaves or figural representations of country life. Mounted on a marble base and standing between 7 and 8 inches tall, they were quite heavy.

Each holder featured either a round frame with a metal pocket in which to place the watch, or a metal hook from which to hang it. Fanciful designs often featured Baroque cherubs.

Each holder featured either a round frame with a metal pocket in which to place the watch, or a metal hook from which to hang it. Fanciful designs often featured Baroque cherubs.

Craftsmen cast less expensive versions in spelter, a heavy zinc and lead alloy, over which they applied a bronze wash or brightly colored paint. They sculpted the originals of animals or single figurines. One example shows a peasant girl carrying a garland wreath. Another depicts a young girl in a sheer, swirling dress which swirls in front to form a tray for cufflinks, watch chain, or coins. Still another example, depicts a parrot either about to land on or take off from a branch and painted a bright chartreuse and red.

The French called them porte montre, meaning “watch stand.” Parisian artisans fashioned ornate watch holders for wealthy travelers visiting Paris on the Grand Tour. Pocket watches were a necessity during this era and fine shops along the Palais Royal specialized in selling unusual and whimsical accessories to hold pocket watches at the end of the day.

The French called them porte montre, meaning “watch stand.” Parisian artisans fashioned ornate watch holders for wealthy travelers visiting Paris on the Grand Tour. Pocket watches were a necessity during this era and fine shops along the Palais Royal specialized in selling unusual and whimsical accessories to hold pocket watches at the end of the day.

These holders came in a variety of decorative styles, from Neoclassical to Regency and on to the opulence of Napoleon III. After the 1860s, watch holder makers explored the styles of the day, such as Rococo Revival and Renaissance Revival. As the 20th century dawned, artisans created holders in the styles of Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts—and by the mid-1920s, Art Deco.

Parisian artisans created some of the most elaborate pocket watch holders. Resembling a larger version of the famed Limoge porcelain box, these became known as a casque porte montre, or pocket watch casket.

By the late 19th century watch holders could be found in a vast variety of shapes and forms. Champlevé, an enameling technique in which craftsmen carved, etched, die struck, or cast troughs into the surface of a metal object, then filled these troughs with vitreous enamel. was especially popular. After the initial preparation, they then fired the piece until the enamel fused, and when cooled, polished the surface of the object. The uncarved portions of the original surface remained visible as a frame for the enamel designs. The name, champlevé comes from the French for "raised field," or background, though the technique in practice lowers the area to be enameled rather than raising the rest of the surface.

By the late 19th century watch holders could be found in a vast variety of shapes and forms. Champlevé, an enameling technique in which craftsmen carved, etched, die struck, or cast troughs into the surface of a metal object, then filled these troughs with vitreous enamel. was especially popular. After the initial preparation, they then fired the piece until the enamel fused, and when cooled, polished the surface of the object. The uncarved portions of the original surface remained visible as a frame for the enamel designs. The name, champlevé comes from the French for "raised field," or background, though the technique in practice lowers the area to be enameled rather than raising the rest of the surface.

Developed in the late 19th Century, these little gems usually often featured a beveled glass box mounted on sculpted brass legs. While some had an eglomise, or back painted view of Paris, most were clear glass.

Developed in the late 19th Century, these little gems usually often featured a beveled glass box mounted on sculpted brass legs. While some had an eglomise, or back painted view of Paris, most were clear glass.

One fine example is a French cristal d' opale rose “hortensia” or “gorge de pigeon,” hand embellished with raised enamel flowers and gilt accents. The rich iridescent pink “hortensia” opaline glass is beautifully supported by delicate ormolu mounts.

One of the more unusual examples of a watch holder originated during the gilded age of Napoleon III. Made in the form of a soldier's helmet which sits on a white marble base, its hand cut gilded brass is meticulously tooled to form the front and back of the hat. The crown of the helmet is of white opaline, with a gilded brass finial. It has a hand tooled gilded mount at the bottom. The helmet top opens to reveal a pocket watch holder mounted with a gilded brass frame. A "U" shaped hook at the top holds the watch while the interior, lined with red velvet, is typical of this opulent period.

One of the more unusual examples of a watch holder originated during the gilded age of Napoleon III. Made in the form of a soldier's helmet which sits on a white marble base, its hand cut gilded brass is meticulously tooled to form the front and back of the hat. The crown of the helmet is of white opaline, with a gilded brass finial. It has a hand tooled gilded mount at the bottom. The helmet top opens to reveal a pocket watch holder mounted with a gilded brass frame. A "U" shaped hook at the top holds the watch while the interior, lined with red velvet, is typical of this opulent period.

Pocket watch holder makers also produced dramatic designs drawn from Nature. On one example, an eagle with its wings outspread and perched on a festoon of arrows and laurel leaves, holds an elongated hook. The top of the piece has a very large cartouche made of two curved cornucopia and a central swan, with neck curved downward, perched on a fleur de lis. A half-moon festoon of laurel leaves flow from one cornucopia to the other.

Also originating in Paris is cast bronze watch holder, designed by 19th-century French artist, Emile Joseph Cartier, featuring a little bird alighting atop a cascading vine of leaves which spill onto the base of the bottom mount. The detail of the little bird—its feathers, sweet expression, and outstretched wings give him a very lifelike appearance. In his beak he holds a curved stick onto which to hang a watch. A half-egg shape bowl, ornamented with leaves and berries, which could hold coins or other jewelry items, rests below him.

Also originating in Paris is cast bronze watch holder, designed by 19th-century French artist, Emile Joseph Cartier, featuring a little bird alighting atop a cascading vine of leaves which spill onto the base of the bottom mount. The detail of the little bird—its feathers, sweet expression, and outstretched wings give him a very lifelike appearance. In his beak he holds a curved stick onto which to hang a watch. A half-egg shape bowl, ornamented with leaves and berries, which could hold coins or other jewelry items, rests below him.

Yet another, made of bronze/metal, features painted detailing to give the effect of fine porcelain. The chubby little body of a cherub with his hands outstretched stands on a cradle made from an egg. He has delicate wings and wears a quiver around his waist, as well as delicate detailing to his fingers and toes and the feathers of his wings. His bow serves as the support for the pocket watch, which hangs within the sculpture design.

Specifically designed and carved as souvenirs are a group of pocket watch holders from towns in the 19th-century "Black Forest" area of Switzerland, Germany, parts of France and Italy, where they pleased travelers on the Grand Tour. These hand carved treasures range from whimsical small bears to large watch holders and wall plaques showing the most realistic anatomical studies of stag, fowl, and "fruits of the hunt."

Specifically designed and carved as souvenirs are a group of pocket watch holders from towns in the 19th-century "Black Forest" area of Switzerland, Germany, parts of France and Italy, where they pleased travelers on the Grand Tour. These hand carved treasures range from whimsical small bears to large watch holders and wall plaques showing the most realistic anatomical studies of stag, fowl, and "fruits of the hunt."

One of the most important French artists of the 1920s, Maurice Frecourt, known for his animal sculptures, produced watch holders in the sleek style of Art Deco. After the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris in 1925, designers embraced the geometric style of Art Deco. One of his watch holders features a stylized bird standing at the edge of a bowl with its wings up and touching and mounted on a black and green veined piece of octagonal marble. He engraved this piece with detailed feathers both in front and in the back.

One of the most important French artists of the 1920s, Maurice Frecourt, known for his animal sculptures, produced watch holders in the sleek style of Art Deco. After the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris in 1925, designers embraced the geometric style of Art Deco. One of his watch holders features a stylized bird standing at the edge of a bowl with its wings up and touching and mounted on a black and green veined piece of octagonal marble. He engraved this piece with detailed feathers both in front and in the back.

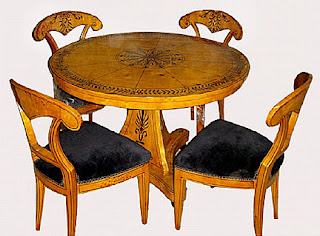

Some pocket watch holders imitated other clock cases, only in miniature. Each evening the pocket watch owner placed his watch into the hole where the clock face would be.

Some pocket watch holders imitated other clock cases, only in miniature. Each evening the pocket watch owner placed his watch into the hole where the clock face would be.

To read more articles on antiques, please visit the Antiques Articles section of my Web site. And to stay up to the minute on antiques and collectibles, please join the over 30,000 readers by following my free online magazine, #TheAntiquesAlmanac. Learn more about "Return to Toyland" in the 2024 Holiday Edition, online now. And to read daily posts about unique objects from the past and their histories, like the #Antiques and More Collection on Facebook.