QUESTION: While I normally associated blonde furniture with the 1950s, I was surprised to see a chest at a recent antique show that the dealer said dated to the early 19th century. She referred to it as Biedermeier, after a design movement in Vienna. Austria. Can you tell me more about this style of furniture/? I’ve never seen anything like it.

QUESTION: While I normally associated blonde furniture with the 1950s, I was surprised to see a chest at a recent antique show that the dealer said dated to the early 19th century. She referred to it as Biedermeier, after a design movement in Vienna. Austria. Can you tell me more about this style of furniture/? I’ve never seen anything like it.

ANSWER: Biedermeier was a German-based decorative movement which spread throughout Europe from 1815 to 1848. The style’s name came from Ludwig Eichrodt and Adolf Kussmaul, who depicted the typical bourgeois of the period under the name "Gottfried Biedermeier."–"Gott" meaning "God," fried" meaning "peace," "Bieder" meaning "commonplace,"_meier" meaning "steward"—in their Fliegende Blatter (Pamphlets), a Viennese journal of the day. However, it wasn’t called Biedermeier until 1886, when Georg Hirth wrote a book about 19th-century interior design and used the word "Biedermeier" to describe domestic German furniture of the 1820s and 1830s.

Biedermeier furniture suited the modest size and needs of comfortable bourgeois households. In middle-class homes, with fewer separate rooms, the concept of the Wohninsel, or "living island," became popular. This made it possible to perform a number of activities in one room—writing, sewing, music making—each characterized by different furniture.

Biedermeier furniture suited the modest size and needs of comfortable bourgeois households. In middle-class homes, with fewer separate rooms, the concept of the Wohninsel, or "living island," became popular. This made it possible to perform a number of activities in one room—writing, sewing, music making—each characterized by different furniture.

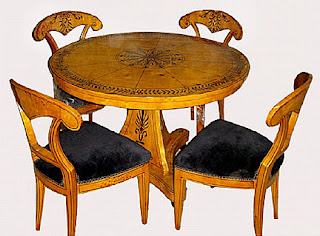

The “living island,” or as it’s known today living room, usually included an ottoman, several armchairs and chairs upholstered in woolen material, sometimes in silk or damask; a round table, a mirror and where possible a glass-fronted case for silver and a piano. The less severe appearance of Biedermeier furniture led to a less formal arrangement of rooms as a whole. Flowers, screens, worktables and knickknacks of all sorts helped to give a sense of family life. The bourgeoisie began to form a personal style, thus creating what’s now known as interior design.

People arranged suites of furniture in the corners, creating areas for eating, chatting, reading, and doing embroidery. Each had a sofa, table and chairs—the most numerous items created in the Biedermeier style.

People arranged suites of furniture in the corners, creating areas for eating, chatting, reading, and doing embroidery. Each had a sofa, table and chairs—the most numerous items created in the Biedermeier style.

Prior to 1830, Viennese cabinetmakers began using mahogany in their furniture, gradually replacing walnut. They gave their finished pieces a light finish, often applying matching stains and finishes to pieces made in walnut, pear wood, and Hungarian "watered" ash.

Cabinetmakers used boards to construct their pieces, which meant that they designed furniture to be seen from the front and executed its ornamentation, such as relief pillars, pilasters, and caryatids, with this in mind.

And by 1830 Viennese craftsmen no longer relied upon French, German, and Italian designers for inspiration. Instead, they used native products, creating pieces based on Directoire and Empire designs, showing a good understanding of form, balance and the use of ornament in gilded bronze.

And by 1830 Viennese craftsmen no longer relied upon French, German, and Italian designers for inspiration. Instead, they used native products, creating pieces based on Directoire and Empire designs, showing a good understanding of form, balance and the use of ornament in gilded bronze.

Viennese cabinetmakers used mostly veneers over a soft wood frame. Inlay served as the main decorative element, featuring the patterned graining of walnut and often reduced to a light-colored border. Sometimes, craftsmen used black poplar or bird's eye maple and colored woods such as cherry and pear also became popular.

Biedermeier furniture makers used gold and black paint to decorate their pieces. They constructed drawers and their housings so perfect and fitted that, even today, when someone pulls out a larger drawer and returns it, the other drawers in the same bank are propelled forward by the force of air created. They also dovetailed, molded and finished drawer linings, making intervening partitions flush on top and paneled beneath.

Biedermeier furniture makers used gold and black paint to decorate their pieces. They constructed drawers and their housings so perfect and fitted that, even today, when someone pulls out a larger drawer and returns it, the other drawers in the same bank are propelled forward by the force of air created. They also dovetailed, molded and finished drawer linings, making intervening partitions flush on top and paneled beneath.

Cabinetmakers also employed less expensive stamped brass wreaths and festoons rather than bronze for decorative effect and gilded wooden stars instead of the elaborate metal ornaments of the Empire style. Sometimes, they chose cheaper, new materials such as pressed paper.

No previous period produced such a wealth of different types of seating, with a myriad of variations on the basic scheme of four legs, a seat, and a back. From 1815 to 1835, Biedermeier craftsmen discovered that a chair could be given literally hundreds of different shapes. Upholsterers padded their creations with horse-hair and covered them with brightly colored velvet and calico. Pleated fabrics covered furniture, walls, ceilings, and alcoves.

No previous period produced such a wealth of different types of seating, with a myriad of variations on the basic scheme of four legs, a seat, and a back. From 1815 to 1835, Biedermeier craftsmen discovered that a chair could be given literally hundreds of different shapes. Upholsterers padded their creations with horse-hair and covered them with brightly colored velvet and calico. Pleated fabrics covered furniture, walls, ceilings, and alcoves.

By the 1840s the Biedermeier style became romanticized—straight lines became curved and serpentine; simple surfaces became more and more embellished beyond the natural materials; humanistic form became more fantastic; and textures became experimental.

An identifying feature of Biedermeier furniture is its extremely restrained geometric appearance. Some furniture took on new roles; for example, a table became the family table, around which chairs were set for evening activities. Or table tops could be placed against the wall in a vertical position. A portable piano had a drawer for sewing things, while the upper drawer of a chest of drawers might be converted into a writing desk.

Next to the secretary, the sofa was one of the most popular of Biedermeier pieces. Rectangular, with a high back and sides, sofas looked deceptively hard. In fact, their depth and solidity made them very comfortable.

Armchairs, too, became more comfortable as changing fashions permitted men to sit back and take their ease.

Armchairs, too, became more comfortable as changing fashions permitted men to sit back and take their ease.

Secretaries were popular as more people wrote letters. While designs varied, most featured a central niche, a mirror, and secret drawers. Cabinetmakers also produced veneered cupboards, vitrines, and wardrobes.

To read more articles on antiques, please visit the Antiques Articles section of my Web site. And to stay up to the minute on antiques and collectibles, please join the over 30,000 readers by following my free online magazine, #TheAntiquesAlmanac. Learn more about "Return to Toyland" in the 2024 Holiday Edition, online now. And to read daily posts about unique objects from the past and their histories, like the #Antiques and More Collection on Facebook.